Our voting

We voted at 7,936 shareholder meetings in the first half of 2025,1 casting votes on 87,399 proposals. We publish our voting intentions five days before each shareholder meeting where practicable, and provide explanations when we vote against the board. Full disclosures are available on our website.

As we are a long-term financial investor, voting is one of our most important rights and tools to support our long-term interests. Our voting guidelines aim to promote sound corporate governance and sustainable business practices. This review summarises our voting in the first half of 2025 and our views on some prominent topics, including board composition and effectiveness, climate risk, and corporate policy engagement.

- 1 Unless otherwise stated, all references to voting patterns in other years also refer to the period from January to June of that year, for comparative purposes.

Understanding the ballot

Our ownership gives us the right to vote at shareholder meetings. Each shareholder meeting typically includes a ballot: a list of proposals put forward for a vote. These proposals fall into two main categories:

|

Proposal type |

Who puts it forward |

Examples |

|---|---|---|

|

Management proposals |

The company’s board of directors |

Electing directors, approving CEO pay, appointing auditors |

|

Shareholder proposals |

An individual or institutional shareholder |

Requesting for a report on climate risks, requesting for separation of CEO/chair roles |

Most proposals that shareholders vote on are management proposals. When we vote, we seek to avoid micromanaging companies. As a starting point, we will support the board, as our representatives. However, we may vote against certain proposals, including the election of directors, where we consider that the board is not able to operate effectively, that our rights as a shareholder are not adequately protected, or that the company’s practices are materially misaligned with the principles expressed in our global voting guidelines. We may also vote in favour of well-crafted shareholder proposals on material matters. These are generally not supported by the board and management.

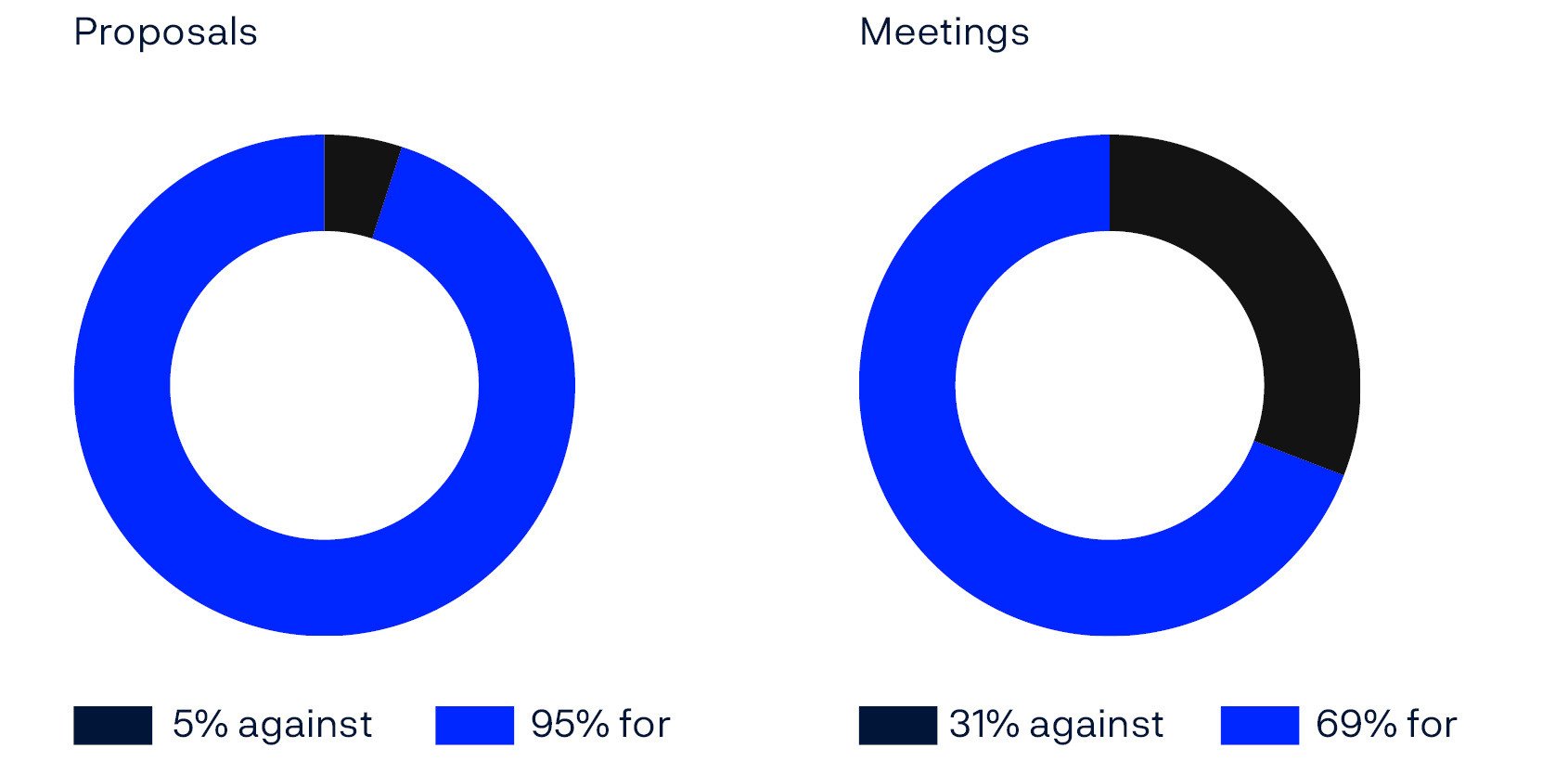

This year, we voted against the board’s recommendation on 5 percent of proposals and voted against at least one proposal at around a third of company meetings.

A typical ballot might include:

- Election of directors

- Approval of executive pay

- Appointment of auditors

- Changes to capital structure

- Shareholder proposals on governance, environmental or social issues

We support management in the majority of cases.

Our approach to voting

We seek to increase the return and reduce the risk of the fund’s investments through responsible investment practices. Voting is one of our most important tools as an owner, but it is most effective when understood in the context of our broader ownership activities. As a shareholder, we engage in discussions with the management and boards of our portfolio companies to better understand and potentially seek to improve aspects of governance, including material environmental and social matters, as well as overall strategy and performance. These interactions, together with our global voting guidelines, inform our voting decisions.

Our voting guidelines are based on internationally recognised standards, such as the G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance, UN Global Compact, UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, and OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. They are also informed by the principles that we have expressed through our position papers on various governance topics, our expectations of companies on material sustainability issues, and our 2025 Climate action plan.

Our positions and expectations reflect the good practices that we wish to see companies adopt over time to reduce risks and increase value. We advocate these practices in our dialogues with companies. Through our voting, we aim to address those companies most misaligned with these positions and expectations, and encourage progress towards these over time. Accordingly, our voting guidelines may include lower thresholds than our global positions or expectations in certain areas, with the intention of raising them in the future.

We aim to be consistent and predictable in our voting decisions, so that they can be anticipated by companies and explained by our voting guidelines and other documentation. To support this, since 2021, we have published our voting intentions five days before each meeting, with a brief rationale referring to the relevant part of our voting guidelines whenever we vote against the board’s recommendations. In 2024, we began disclosing expanded voting rationales for selected votes, to provide additional transparency.

Being consistent and predictable does not mean that we vote the same way every year on every issue, or even at every company. When applying our voting guidelines, we consider local market context and, where possible, company-specific circumstances, including insights from our portfolio managers in cases where we have a significant active holding in a company. Our internal portfolio managers have deep, company-specific knowledge, which is a valuable resource when we vote. In 2025, portfolio managers participated in voting decisions at 533 companies, representing 55 percent of the value of our equity portfolio.

Spotlight

Virtual versus hybrid annual general meetings

The format of general shareholder meetings has changed significantly in the years following the COVID-19 pandemic, when many jurisdictions made provisions to allow virtual annual general meetings.

According to a recently published OECD report, as at the end of 2024, 45 out of 52 jurisdictions allow virtual-only meetings, and 49 allow hybrid formats. Virtual-only meetings are now popular in the US and Canada, South Africa and the Middle East, while hybrid meetings are preferred in Australia. In-person meetings, with or without digital access, have resumed as the primary format in Singapore, the Netherlands and the UK.

While introducing virtual access to meetings can streamline company procedures and reduce costs, it also risks undermining transparency and shareholder engagement. We are concerned about approaches that, in practice, limit shareholders’ ability to participate, such as Italy’s introduction of closed-door meetings conducted exclusively by proxy.

Our preference is for companies to maintain the possibility of in-person participation via hybrid formats. However, we acknowledge arguments in favour of virtual-only approaches, particularly where this lowers practical barriers to participation by international shareholders and/or domestic shareholders in large countries.

How we voted in 2025

Overall, we voted against a similar, small proportion of companies across different proposal types as in previous years, reflecting our consistent approach.

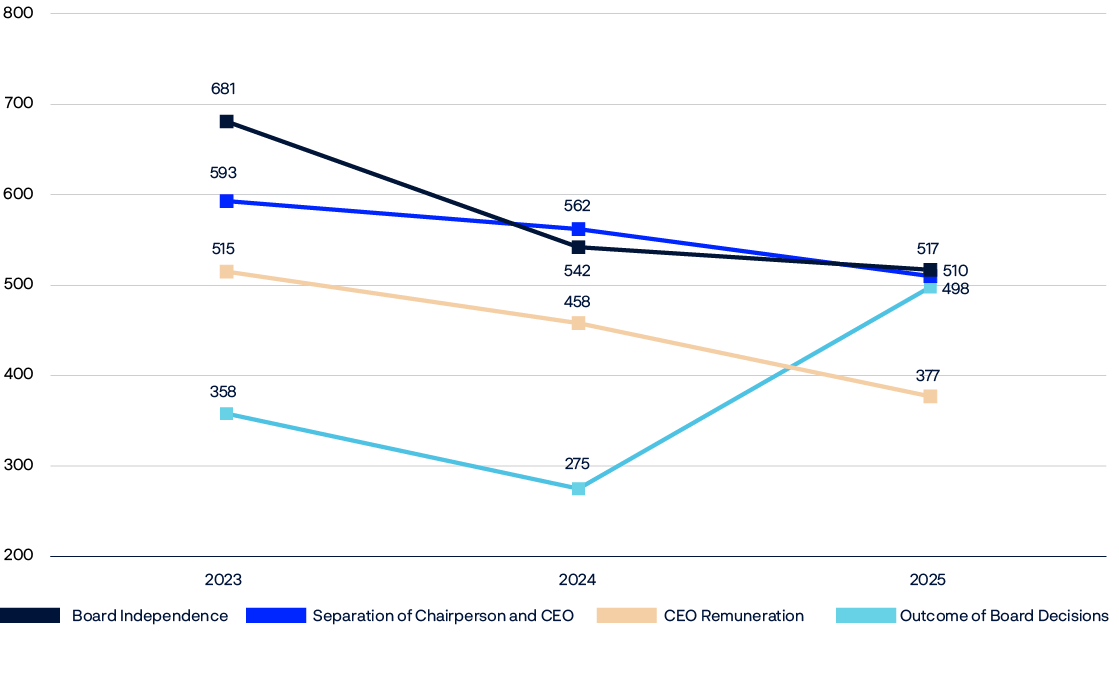

In some key areas, such as CEO pay, board independence and election of a combined chair/CEO, we voted against fewer proposals in 2025, reflecting evolving company practices, regulatory developments and changes to our portfolio. Meanwhile, new guidelines on cross-shareholdings at Japanese companies drove a spike in votes against boards for the outcome of their decisions.

The number of proposals where we have voted against management on select rationales over the last three years. See Appendix 1 for an overview of the percentage of companies voted against across all rationales.

Management proposals

Most items we vote on are management proposals, namely proposals submitted by the company’s board of directors. Items put to a vote vary by jurisdiction, but typically include the election of directors, approval of CEO pay, appointment of auditors, and changes to the company’s governing documents.

Board composition and effectiveness

We generally own a relatively small percentage of the companies we invest in, and we delegate most decisions to their boards and management teams. Having boards that effectively represent our interests as shareholders is therefore critical to us and a topic we continuously engage on with companies. This is directly reflected in our voting, as electing directors is one of our most important shareholder rights.

Director elections account for nearly four in ten of the resolutions we vote on. We expect board members to act independently and without conflicts of interest, to have the right balance of experience and skills to carry out their duties, and to be accountable for their decisions and oversight.

Board independence

We view board independence as a core component of good governance. To balance competing demands, a board needs a sufficient level of independence and objectivity to be well-equipped to guide strategy, oversee management and be accountable to shareholders. In most markets, we expect at least half of board members to be independent, with some exceptions based on market context.

Overall, we are seeing continued improvements in levels of board independence in developed and emerging markets. We saw a 5 percent reduction in votes against directors or other relevant proposals this year due to independence concerns, compared to the same period in 2024. This includes Japan, where improvements in board independence led to a 10 percent drop in votes against directors this year compared to 2024, and a 34 percent drop compared to 2023.

Separation of chair and CEO

We continue to have concerns about the roles of chair and CEO being held by the same person on company boards. We have long advocated the separation of chair and CEO and believe that a non-executive chair is better positioned to guide strategy, oversee management and promote the interests of shareholders. In cases where separation is not considered to be feasible in the near term, we expect companies to clearly demonstrate how any conflicts of interest are being mitigated.

81 percent of the companies we voted against for this reason are in the US and South Korea, where a combined role remains common. In the US alone, we opposed the chair/CEO at 305 companies, which is around 20 percent of the US companies where we voted. This number is down slightly from 320 companies in 2024, reflecting relatively slow change on this issue.

Board gender diversity

In our pursuit of effective boards with the diversity of skills, experience and perspectives necessary to fulfil their duties, we view having sufficient representation of each gender as an important indicator of board quality and decision-making.

Our expectation is that each gender represents at least 30 percent of the board. Recognising that the dynamics that influence the representation of women on boards are heavily impacted by local market context, we are implementing this expectation progressively over time. We will generally vote against boards that do not meet the following minimum thresholds:

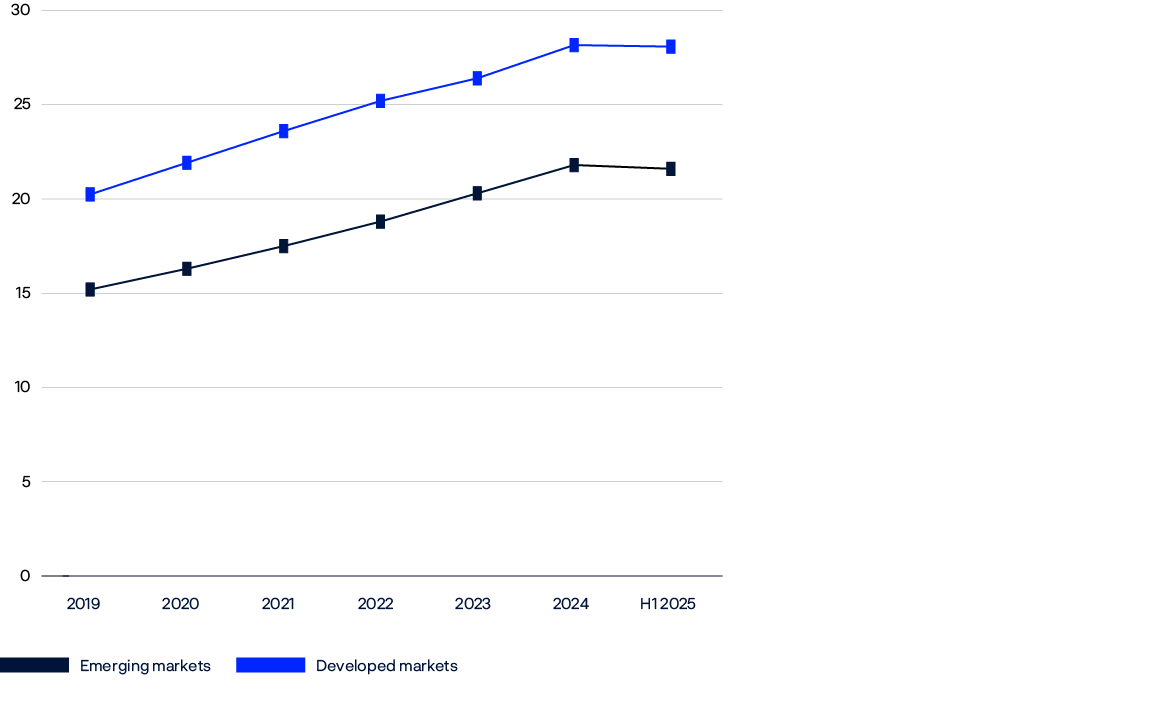

- In developed markets, we expect at least two representatives of each gender. 91 percent of companies met this threshold in 2025, consistent with the level seen in the first half of last year.

- We make exceptions in certain developed markets – namely Japan, Singapore, South Korea and Poland – which have seen slower progress. In these markets, we require at least one representative of each gender. 84 percent of companies met this threshold this year, up from 78 percent last year.

- In emerging markets, we introduced a new requirement in 2024 of at least one representative of each gender. We were encouraged to see that 92 percent of companies met this threshold in 2025, roughly the same as last year.

The average percentage of women on boards in our portfolio per market classification.

Our data continue to show a positive trend in the progress of women on boards in our portfolio this year, although the rate of improvement has slowed. This deceleration reflects both varying market progress and improved access to director data for smaller companies and markets with historically less gender-balanced boards.

Our guidelines on board gender diversity for all markets will evolve over time, with the aim of moving towards our expectation of 30 percent representation of each gender. Currently, 61 percent of boards across our portfolio (53 percent in developed markets and 78 percent in emerging markets) have yet to meet this, highlighting the progress still required.

Board accountability

We believe that boards should be accountable, in their oversight role, for ensuring that companies manage material risks and do not contribute to unacceptable corporate governance, environmental or social outcomes. In a small but important number of cases, we vote against directors and/or boards where we believe they have failed to fulfil their duties.

In the first half of 2025, we voted against board members at 201 companies due to governance concerns. A key driver was our strengthened stance on cross-shareholdings in Japan. Under our new guidelines, we voted against board members at 112 Japanese companies where we assessed that cross-shareholdings were excessive and not aligned with shareholder interests. In other cases, votes were driven by concerns that boards had failed to respond adequately to low support for pay proposals in the previous year, or where a company had experienced material failures of governance, risk oversight or disclosure, or a breach of fiduciary responsibilities.

We also vote against a small but important number of boards due to concerns relating to oversight of material sustainability risks. Before voting against, we will seek to engage with companies to better understand their practices and ensure they understand our expectations. We consider voting against directors to be a point of escalation when engagement outcomes or very specific events are unsatisfactory.

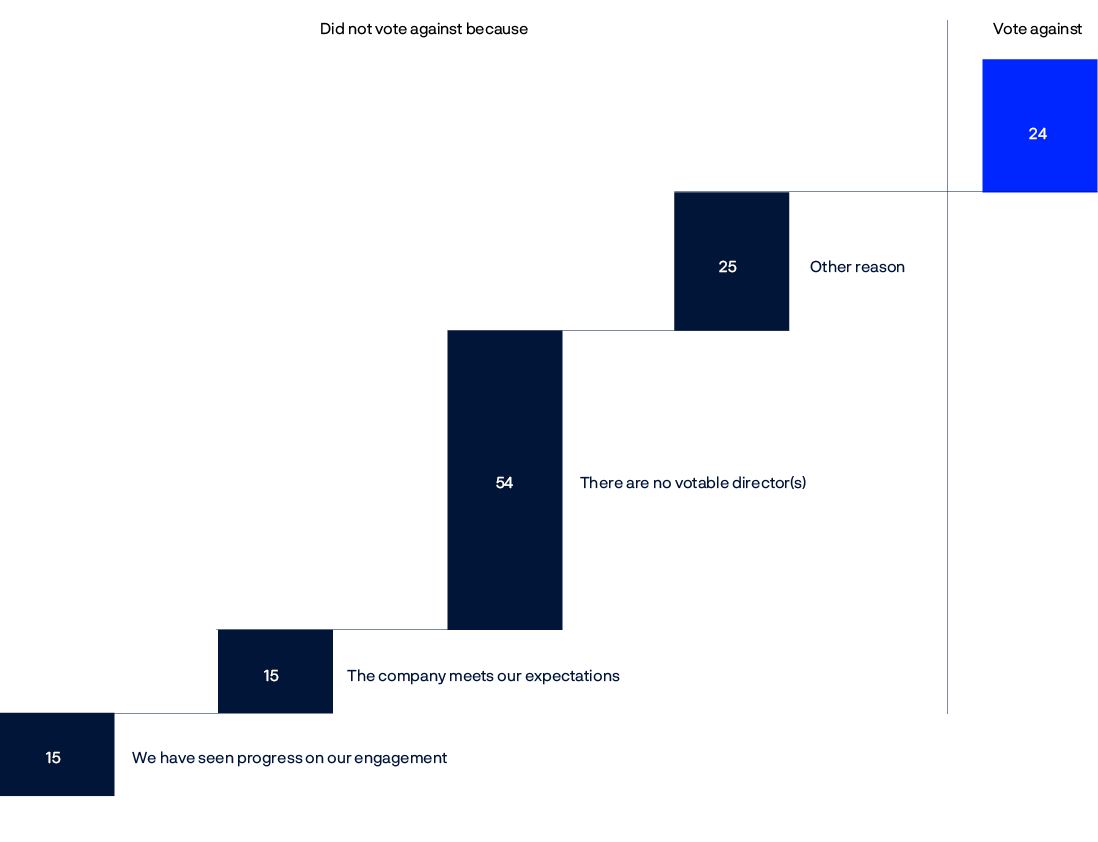

This year, we identified 182 companies as having heightened risks of sustainability failings. We evaluated each case, considering factors such as the company’s responsiveness to engagement, what we had learned from such interactions, any improvements made over time, and forward-looking commitments. Following this assessment, we voted against 24 companies in the first half of this year, compared to 26 in 2024. Of these votes, 21 were due to material failures in the oversight, management and disclosure of climate change risks, while three were due to social risks.

Our assessments on board accountability for sustainability risks where the company had an annual general meeting in first half of 2025.

CEO pay

How a company’s management team is incentivised and rewarded can have a significant influence on decision-making and performance over time. This is particularly important in the case of CEOs, who we believe should be paid via simple packages primarily made up of a cash salary and shares that vest after five to ten years, regardless of resignation or retirement. This require them to build up and hold shares over the long term, aligning their interests with long-term shareholder value. We believe this approach also reduces the risk of unintended consequences that can arise when a significant portion of pay is based on achieving various performance metrics, given the difficulty of identifying those that effectively drive long-term outcomes.

|

Common CEO pay components |

Description |

Typical time horizon |

|---|---|---|

|

Base salary |

Fixed pay, usually given in cash. |

Immediate |

|

Short-term incentives (STIs) |

Bonus payments for achieving annual targets. Paid in cash and/or shares. |

1 year |

|

Long-term incentives (LTIs) |

Shares (conditioned on time and/or performance targets) and/or share options awarded after a set time frame. |

1-5+ years |

|

One-off awards |

Special bonuses that reward a particular achievement, compensate for awards given up when joining the company, or to retain an executive. |

Variable |

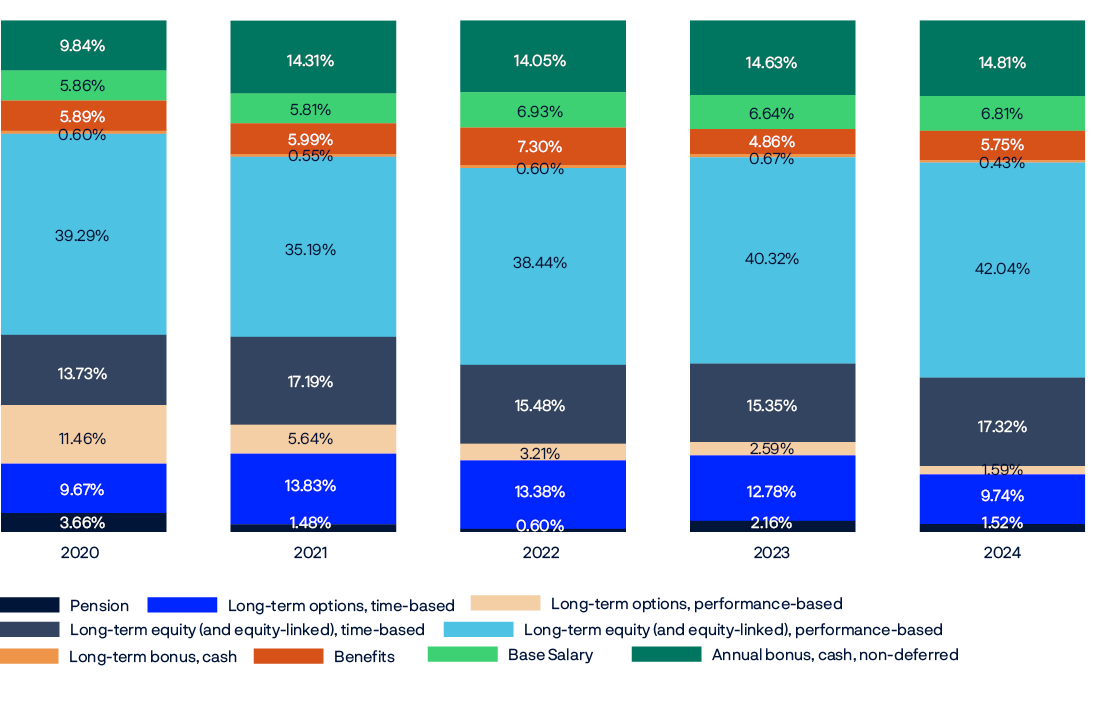

Currently, relatively few companies around the world use the simple structures we advocate. Many combine a cash salary with short- and long-term incentive schemes, paid partly in cash and partly in shares, which are released to executives based on a set of complex multi-year criteria. The following graph shows the pay components of US CEO pay over the past few years.

Average pay element by fiscal year as percentage of total pay element.

Breakdown of proportion of different components in disclosed pay for S&P 500 CEOs. Norges Bank Investment Management current holdings for fiscal years 2020–2024.

We do not think it would be constructive to oppose the majority of CEO pay packages solely because they do not yet follow our preferred model. We therefore take a pragmatic approach in our voting guidelines to identify the packages that are most materially misaligned. For example, we will generally not support pay packages that:

- Award CEOs shares over a timeframe we consider too short-term.

- Include substantial one-off awards, such as ‘golden hellos’ and severance payments.

- Appear unduly costly, where we have concerns about the overall design of the pay scheme, or where alignment with performance is lacking.

- Are not appropriately adjusted by the board in response to shareholder concerns raised in previous years.

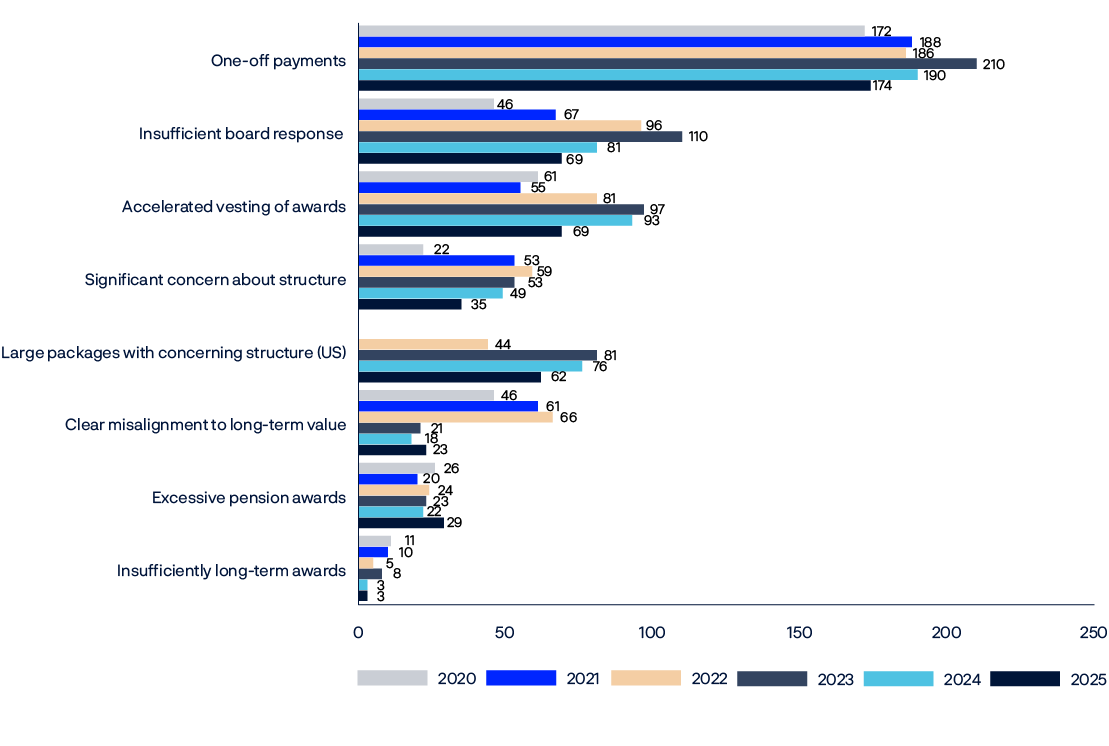

In the first half of 2025, we voted against a total of 265 pay packages globally, compared to 314 in 2024. The US market continued to represent around four in ten of these votes (42 percent of votes against executive pay plans in 2025, versus 39 percent in the same time period in 2024).

Overall, we saw fewer concerning practices this year and voted against fewer packages for reasons including one-off awards, accelerated vesting of awards, insufficient board response to low support for pay in previous years, and structural concerns. We continued to apply a stricter assessment to the largest US packages, which we currently define as those worth 25 million dollars or more, after making an inflationary adjustment. We reviewed fewer packages this year but voted against a higher proportion of packages assessed – 60 percent in 2025, compared to 45 percent in 2024.

Reasons why we voted against companies on CEO pay from H1 2020 – H1 2025.

Spotlight

CEO pay in the UK

The UK is considered to have a robust corporate governance regime with well-established market norms for CEO pay. This includes binding shareholder votes on pay policies and common pay structures that emphasise long-term share ownership, such as long-term incentive plans that pay out in shares after five years, annual bonuses that typically pay out partly in shares to be held for a number of years, and a required shareholding level that CEOs must reach and maintain while they are at the company. Since 2019, most UK companies have also required CEOs to maintain a certain shareholding for a period after they leave their roles – typically two years.

We consider this a very positive practice that aligns well with our preferred approach to CEO pay.

However, this established framework has come under pressure. In recent years, some UK companies – particularly those with US operations or a US-heavy peer set – have argued that differences between UK and US pay levels are hindering their ability to compete for talent. Some have proposed changes to CEO pay packages that aim to reduce this ‘transatlantic pay gap’. We have supported certain proposals where we believed there was a reasonable case for increasing pay, provided the packages maintained or strengthened the emphasis on long-term share ownership for CEOs.

Shareholder proposals

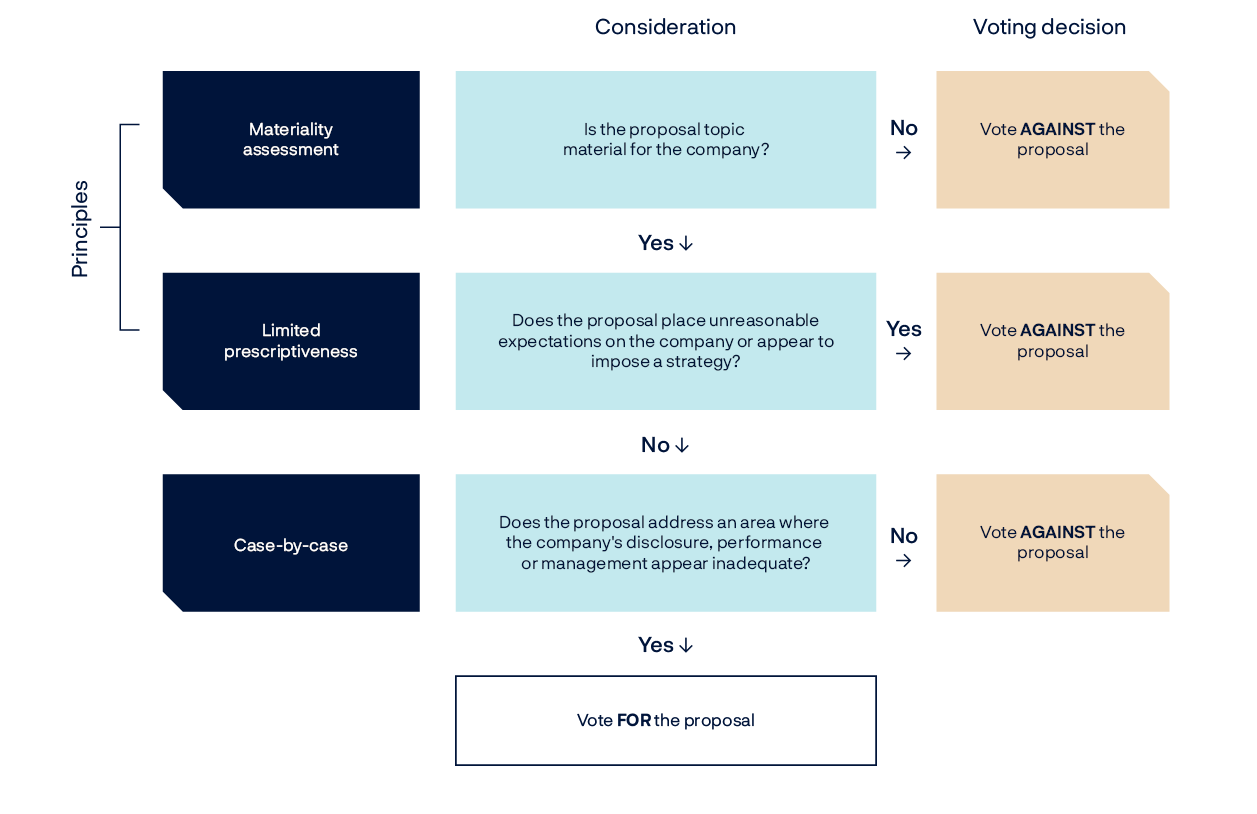

If a proposal submitted by a shareholder is included as an item at a company annual general meeting, shareholders will be able to vote for or against its adoption. We conduct a case-by-case assessment of each shareholder proposal, considering its alignment with our principles and its relevance to long-term value creation. Our three-stage framework evaluates the materiality of the issue to the company, the prescriptiveness of the proposal, and its scope, including any tangible actions the company has taken.

We evaluate the company’s current practices and disclosures, compare these to peers and market standards, and consider any dialogue we have had with the company. Generally, we support proposals that highlight material gaps in disclosure, strategy or performance, especially where companies lag peers or our published expectations. However, we are more cautious about proposals that impose rigid demands or encroach on the board’s responsibility for strategy and day-to-day management.

As with all our voting, we aim to be consistent but may not vote the same way across different cases. Each year, companies make changes to their practices, standards evolve, and the risk picture changes.

Our assessment framework for shareholder proposals.

Spotlight

A varied global landscape

The nature and volume of shareholder proposals vary greatly across markets. In most jurisdictions, shareholders must meet certain requirements relating to the size or duration of their holdings to be eligible to file a proposal. In some, proposals are structured as binding resolutions implemented via changes to a company’s constitution or articles of association. In others, proposals are non-binding (advisory) items.

Filing thresholds affect what we see on the ballot. Low thresholds and a wider scope of permissible topics largely explain why most shareholder proposals are filed in the US and Canada. On the other hand, we see relatively low numbers of shareholder proposals on the ballots of Indian companies, partly driven by the high ownership requirements for filers.

In Japan and Australia, shareholders can only submit binding proposals, typically by proposing changes to corporate governing documents. Conversely, in the US and Canada, proposals are mostly advisory. This matters for how we assess proposals. Even if shareholders raise a reasonable request on a material issue, we may find it too prescriptive to change the company bylaws to address it.

|

Country |

Filing threshold1 |

Binding status |

Global share of |

|---|---|---|---|

|

US |

USD 2,000 held for 3 years, |

No (mostly advisory) |

65% |

|

Japan |

1% of voting rights or 300 voting units (minimum 6 months holding) |

Yes (must propose amendment to Articles of Incorporation) |

8% |

|

Canada |

1% of voting shares or shares worth at least CAD 2,000 (minimum 6 months holding) |

No (mostly advisory) |

7% |

|

Australia |

5% of voting rights or 100 shareholders |

Yes (must propose amendment to Articles of Incorporation) |

3% |

|

UK |

5% of voting rights or 100 shareholders |

Depends on resolution type -rarely binding |

1% |

|

India |

10% of voting rights |

Yes |

<1% |

1 Source: ACGA 2025

2 Percentage of global environmental and social shareholder proposals filed in the stated country since 2020, based on companies in the fund’s portfolio.

A different year for shareholder proposals

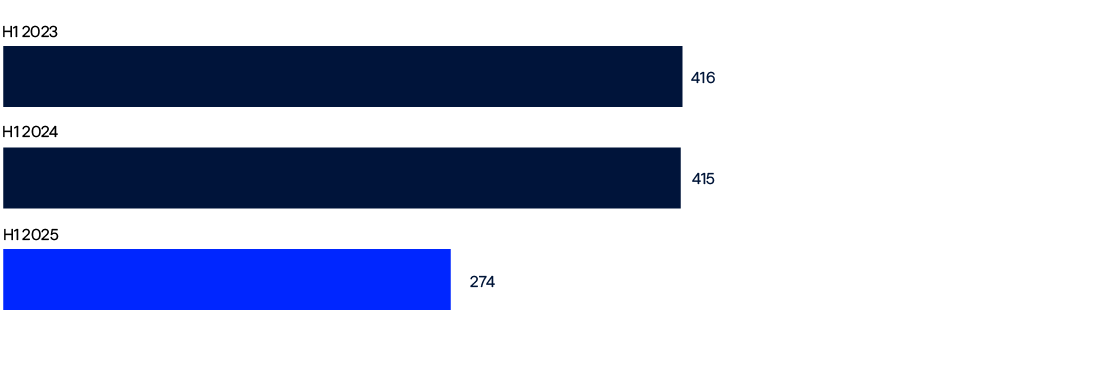

This year, the landscape for shareholder proposals changed. We saw a notable drop in the number of environmental and social proposals making it to the ballot – 274 in the first half of this year, compared to 415 for the same period last year. This suggests more proposals were withdrawn or blocked. Our analysis shows that market-level support is at historically low levels.

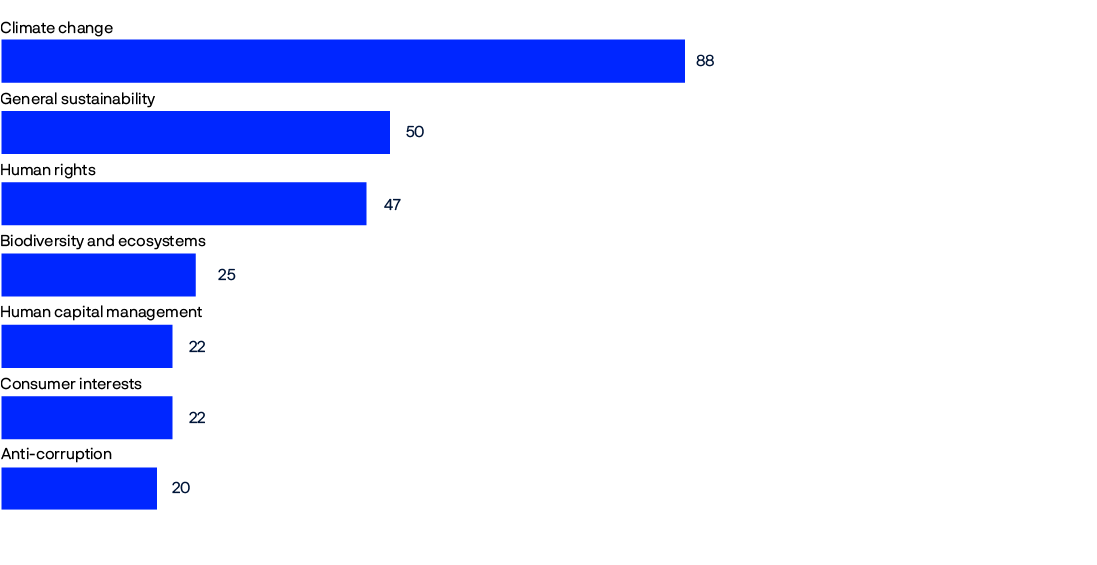

Number of environmental and social proposals.

Number of environmental and social proposals per topic H1 2025.

Companies are navigating an increasingly polarised landscape, with some facing competing shareholder proposals – one calling for the removal of certain policies, and another urging that those same policies be strengthened. At the same time, the pool of proponents has narrowed: more than a third of sustainability-related proposals in 2025 were filed by just five proponents.

In our engagement discussions, some companies have expressed feeling caught in the middle of political tensions, noting that it is difficult to discern shareholder expectations amid the noise, especially given the more cautious approach of many shareholders.

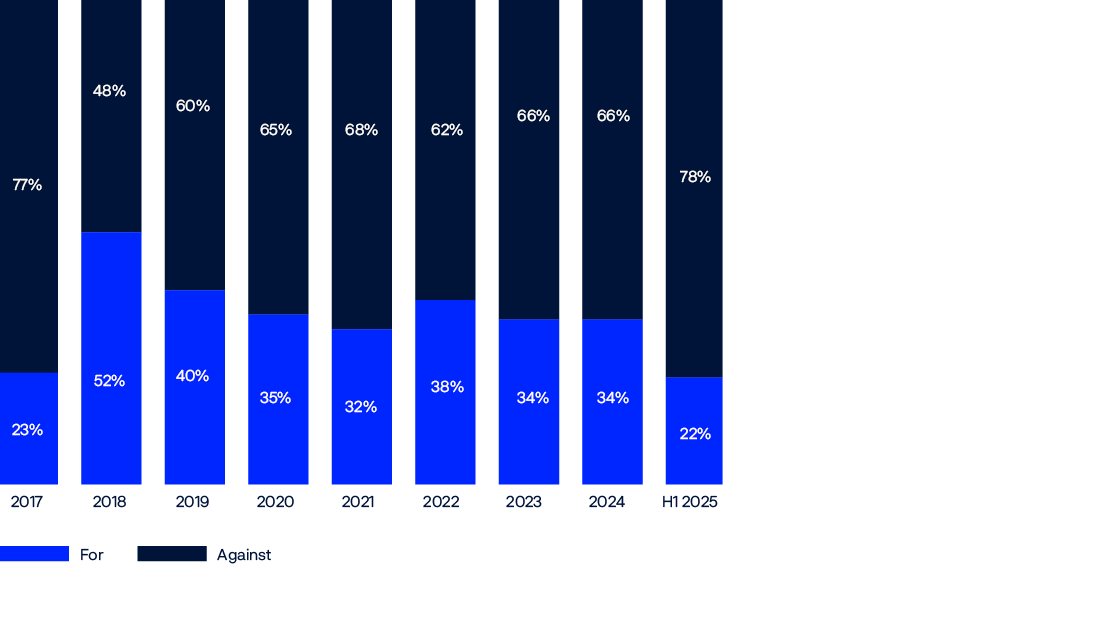

This year, we supported fewer sustainability-related shareholder proposals overall, reflecting what we considered to be a decline in the quality of the underlying proposals, with many appearing misdirected or lacking materiality.

However, we continue to view well-structured shareholder proposals as a useful tool for escalating material concerns to the board, particularly where engagement has not led to sufficient progress. Support for proposals – even when non-binding – can prompt boards to act, especially when supported by a large share of the vote.

Our level of support over the years.

Corporate policy engagement

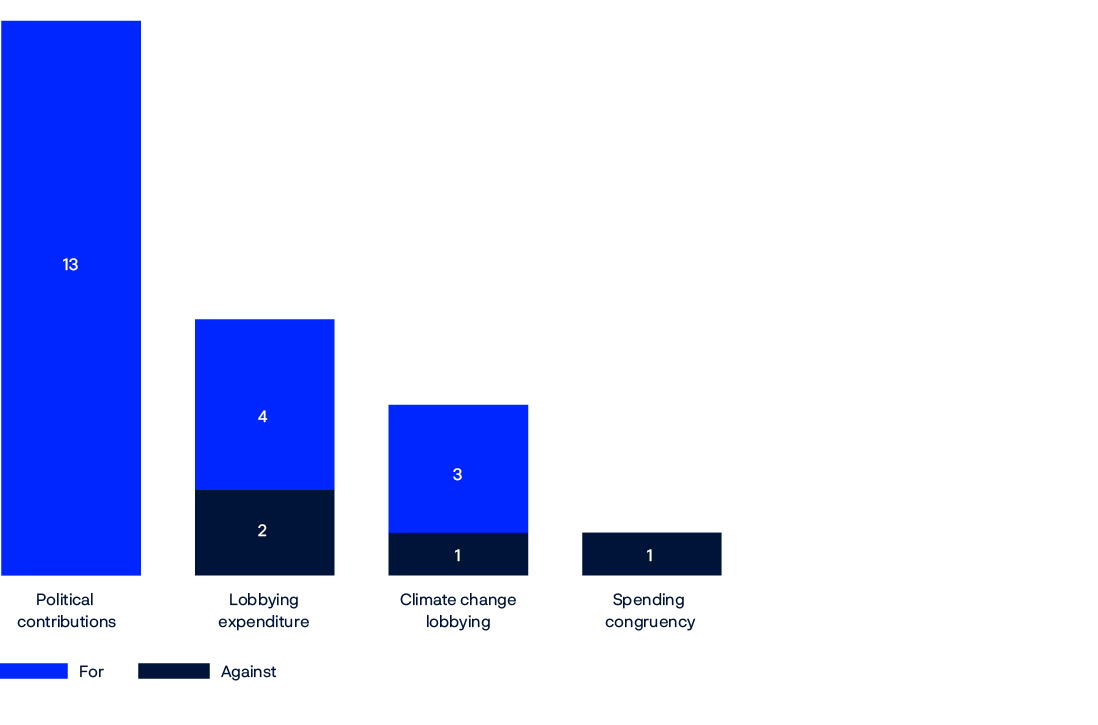

Corporate policy engagement was one of the most popular proposal topics in the first half of 2025. Of the four shareholder proposals that received majority support this year, all of them related to political contributions.

We published our view on responsible corporate policy engagement in August 2024. We believe transparency and robust oversight are the cornerstone of responsible corporate engagement in the policymaking process, and that this engagement should align with companies’ stated policies and sustainable value creation. In line with our view, we broadly support proposals that call on companies to enhance their disclosures and to align their policy activities with the objectives of the Paris Agreement. This led us to vote in favour of more than 80 percent of such proposals in the first half of 2025.

How we voted on corporate policy engagement shareholder proposals.

Climate

Climate remains a prominent shareholder proposal topic and an important focus for us. While the absolute number dropped from 116 proposals in the first half of last year to 88 in the same period this year, climate proposals actually represented a higher percentage of all shareholder proposals in 2025. Our support decreased from 28 percent to 20 percent this year, reflecting reduced alignment of the proposals with our expectations.

As stated in our 2025 Climate action plan, we believe that the fund stands to benefit from an orderly transition towards global net zero emissions that fully addresses the risks associated with climate change. We expect company boards and management to manage climate risks in a way that is consistent with our climate change expectations.

While we advocate sustainable business transformation, we also recognise the significant challenges faced by many companies and respect their operational independence and need to adapt to their specific contexts. The energy transition will take decades, unfold differently across markets and industries, and require companies to make complex decisions under uncertainty. It is in this context that we analyse climate proposals and may vote against overly prescriptive shareholder proposals, such as blanket bans on fossil fuels. We support climate-related proposals when they are financially material and aligned with long-term value creation.

Important information: This disclosure is provided for educational and information purposes only. It does not constitute advice and should not be taken as a recommendation, a forecast or an instruction on any matter, including whether any relevant third party should buy, sell or retain shares, or how any third party should exercise any voting rights they may have. Any person who wishes to obtain advice should seek this from a professional adviser. This disclosure is not a proxy solicitation and is not intended to influence the vote of other shareholders. No reliance should be placed on this information or its accuracy, and Norges Bank accepts no responsibility or liability for any action taken or not taken on the basis of this information. Any relevant third party should form their own views based on their own analysis of the relevant facts and circumstances. Norges Bank has no duty of care in respect of any third party who decides to view this disclosure and undertakes no duty to update the information provided herein.

We will not apply any policies discussed herein in circumstances where we believe that implementing or following such policies would be deemed to constitute seeking to change or influence control of a portfolio company with securities registered on an exchange regulated by the United States Securities and Exchange Commission.

Appendix

|

Concern leading us to vote against companies (all topics) |

Percentage of companies opposed |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

H1 2025 |

H1 2024 |

H1 2023 |

|

|

Anti-takeover measures |

1.3 |

1.3 |

1.6 |

|

Auditor |

2.3 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

|

Board independence |

5.3 |

5.7 |

7.0 |

|

Board structure and nomination process |

2.6 |

2.9 |

2.9 |

|

CEO remuneration |

4.6 |

5.2 |

5.6 |

|

Changes to bylaws or charter |

2.9 |

3.9 |

2.7 |

|

Board diversity |

1.6 |

2.1 |

2.7 |

|

Financial statements |

4.5 |

4.4 |

4.5 |

|

Independence of main committees |

3.2 |

3.6 |

3.8 |

|

Meeting requirements |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

|

Mergers, acquisitions and other corporate transactions |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

|

Multiple share classes |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

|

Outcome of board decisions |

3.2 |

1.5 |

1.9 |

|

Related party transactions |

1.3 |

0.9 |

1.1 |

|

Separation of chairperson and CEO |

7.0 |

7.4 |

7.3 |

|

Share issuance |

1.2 |

1.1 |

1.3 |

|

Sustainability reporting |

0.7 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

|

Time commitment |

2.7 |

2.8 |

3.7 |